How to hold a

Septuagesima Eve or Farewell Alleluia Party

Septuagesima

Eve is the lychgate of Lent – that way station marking entry into the

churchyard, ere on Ash Wednesday we pass through the very portal of the church

into Quadragesima Abbey, as it were, where for forty days and nights we will

redouble our penances and in monkish wise undertake ascetic exercises,

cloistering our souls from the busy world till the happy day of Resurrection.

Now a lychgate,

as all men know, is a gate overshadowed by a roof, symbolic of Him Who is the

Gate of the sheepfold, Himself overshadowed by the Holy Ghost, whereto a body

brought for burial is carried, and the first part of the funeral conducted,

before it is brought into the church. Hence, when as at first Vespers of

Septuagesima the Alleluia is laid aside, in a manner its death is to be

represented – just as the corpse, in shroud y-wrapt, ought be plonked down in

the lychgate.

Moreover, a

wake ought be held, for to mourn dead Alleluia (dear maiden), and, to prevent

enormities, Alleluia ought be buried straightway. For this reason, on

Septuagestima Eve, Alleluia is buried after Vespers; and, both before and after

these affecting services, cocktails in the liturgical colours ought be served

nearby.

Before the

obsequies, as suitably accoutred guests arrive for this devotional pastime, the

gracious host ought present each one with a green cocktail to fittingly conclude

Epiphany-tide. It is not permitted to colour the drink with green food

colouring – note in particular that green-tinted Guinness is an abomination,

and one reserved in any case for St Patrick’s Day. Instead, cunning

combinations of sundry decoctions, liqueurs and elixirs are to be employed. This

verdant beverage, and all subsequent top-ups, should be consumed before the

commencement of First Vespers of Septuagesima.

One

should wait

until all guests arrive before starting Vespers; it is most disruptive

to have

people scrabbling for chairs and music, and attempting to join in psalms

half-way through. Note that, if the land be laid under interdict, the

doors must be closed, and the Office recited on a low note; which will

somewhat dampen the spirit of the occasion.

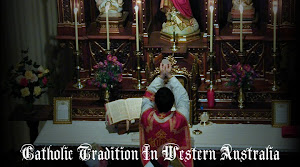

For Vespers, a mediæval chapel (Gothic or Romanesque) is required (every home

should have one), or at least a large space, fittingly tricked out, with two rows

of chairs facing each other. Do not use narrow hallways: otherwise there can be

the risk of accidental concussion at every Gloria Patri. While purists

may gasp in horror, it is suggested that the two choirs be mixed (with men and

women on each side), lest the volume be too unequal.

It is

preferable, whether there be a permanent or temporary chapel, to celebrate

Vespers before a dressed and decorated altar (eastward facing) upon which the

requisite number of lit candles burn. The Alleluia should be hung on the altar

front for all to observe clearly. If no medieval tapestry is available, a large

piece of cardboard, made to resemble parchment, with the Alleluia y-writ

thereon in clearly visible lettering (employing a flowing font with serifs) will

suffice, and may be attached to the altar with concealed tape if no hooks are provided.

Benedicamus Domino with doubled Alleluia having been

sung, and Vespers concluded with the Fidelium

animæ (or, if a bishop be present, after he has imparted his

blessing – if several prelates be present, the highest-ranking blesses

unless suspended a divinis),

immediately two or four of the youngest present (juniores priores) approach the altar, make due reverence, detach

the Alleluia in comely fashion, and gently lay it flat, text facing up, on the

waiting bier, which has been prepared earlier.

Carrying their

cargo with deserved decorum, these bearers then lead a funereal procession out

from the chapel, through the house, and around the garden to the grave prepared

(which must have been suitably decorated with purple flowers, and supplied with

a handy pile of stones nearby). Meanwhile all sing the hymn Alleluia dulce carmen, preferably in polyphony,

repeating its verses as necessary until Alleluia be buried into the grave.

Having

assembled at the graveside, the officiant first rolls up the Alleluia if

necessary, then with sober deportment deposits it into a coffin or other apt

receptacle. After sealing this, he lowers it into the grave. All present then

process past this resting place of dead Alleluia, each one laying a stone on

top as they pass, thus building a cairn while still singing. All depart the

grave in solemn silence after a most liturgical pause.

Following the

obsequies, as expeditiously as possible, the host and his attendants (as it

were the celebrant and his ministers) should make and distribute purple

cocktails to the guests. On no account are any left-over green cocktails to be

consumed, under pain of serious sin and excommunication reserved to the

Apostolic See. Nonetheless, exceptions to this rule are allowed for those who

are allergic to the purple cocktail; or those who are only permitted one

alcoholic beverage and who arrived too late to finish their drink before

Vespers; or those holding a Papal indult or immemorial privilege: no others.

During the

mixing these purple cocktails, it is fitting for guests to retire and shed

their green garments in favour of purple ones, if possible. Men of limited

imagination may choose simply to change their neck tie. Since the liturgical portion

of the evening has been completed (as Compline will be recited in private),

guests may innocently disport themselves henceforth as befits any polite social

gathering, taking care to remember that utterance of the ‘A’ word is strictly

forbidden.